product v distribution, and a new framework for PMF

Welcome back!

The ‘SG&A’ification’ of tech

The last decade has seen startups’ competitive edge shift from the ability to build technical products to increasingly, gaining a wedge into distribution. This is evident with recent winners such as Uber, Airbnb and Snowflake, who’s cost bases are heavily skewed towards SG&A. This trend has been accelerated by the lower barriers to software creation, competition and the overbearance of entrenched platform companies.

This post explores how that’s happened, why it's increasingly crucial for founders to have core competencies in distribution and a product-market fit framework to help founders structure their scaling.

Shifting Risk from Tech to Distribution

Historically, venture risk funded the high upfront costs of building technical products - these were predominantly physical servers and engineering talent.

But since then, the addressable market of software companies has increased, as have the 'picks and shovels' companies who have largely abstracted away the tech stack, from AWS, APIs to no-code. Cloud infrastructure has turned much of startup capex into variable costs, lowering barriers to starting a company - though arguably increasing competition and costs to scale.

Investors had previously been focused on 'network effects' businesses, which is a mechanism for vastly easier distribution and defensibility through viral growth. Unlike the market ‘pull’ we saw through the dotcom area, startups are increasingly shifting capital from R&D to SG&A. The scarcity of remaining large-scale network effects still to be exploited has renewed investors' appetite for enterprise solutions and labour driven marketplaces, two SG&A-heavy verticals. Additionally, we have seen the founders’ target more operationally intensive and SG&A heavy industries such as Real Estate, Healthcare, Mobility etc.

There are some new ‘diseconomies of scale’ on the acquisition side, with the Google/Facebook advertising duopoly being dominant, and limited capacity for new surface area in consumer especially leading to zero-sum acquisition amongst startups. The scarcity in many verticals has partially shifted away from technical talent building software to getting sustainable distribution advantages. There are fewer ‘blitzscaling’ based companies, relying on speed for a land grab. Interestingly, Snowflake’s IPO revealed it’s heavy skew towards SG&A;

“.....of all public SaaS companies, Snowflake spends most on Sales & Marketing as a percentage of revenue at 70%.”The Generalist

You might assume from this, that really the only thing that matters is finding scalable distribution. Well, no. Product is and always will be key, (see my ‘product pickers’ post) though today a great UX, interface and cross-platform operability have become table stakes for what is an increasingly busy acquisition landscape.

"can a startup get distribution before an incumbent gets innovation?" Alex Rampell

The current focus on distribution advantages has given rise to a new subset of marketing efforts, from growth hackers, community-first companies, ‘building in public’, bottom-up adoption and product-led growth, where the product itself has inherent growth loops. Do not expect this to change any time soon.

Nowhere is a distribution advantage more evident, and more difficult for insurgents to get a wedge in than with the current crop of platform companies.

platforms-rules-everything-around-me

This is not a trend but more of a cycle, legacy players such as Microsoft, Cisco and Oracle, have been clinical in their ability to hoover-up scale, through not only distributing through existing products but also acquiring competition. Maybe the best example of this is Microsoft's late pivot to the web, which saw them pre-install Internet Explorer on Windows, edging out Mosaic until they were hauled in front of the DoJ (see the US v Microsoft)

Heck, even Google, the famed product house, was strategically aware early on of the advantages of gaining distribution advantages. Their search engine, which they grew in part through paid distribution within web browsers, gave them advantages for the Ads engine (DoubleClick acq.), Maps (Where2 acq.) and Docs (acq. Writely). Let's take a look at some other recent examples;

Apple Music v Spotify

When Apple Music launched in 2015, there were over 700m iOS users globally. Apple's ability to pre-install Music on iOS devices forced visibility of Music. Additionally, by pushing visibility of Apple Music through their App Store, instead of rival products, they vastly increased their chances of adoption. This, unsurprisingly, culminated in an antitrust lawsuit between the two parties (more here).

Apple converted as many customers in their first year, as Spotify had in their first seven. Whilst Apple Music hasn't won out, largely due its inferior product offering and secondary brand positioning, it has clearly managed to leverage its operating system in order to drive scale.

Microsoft [Skype] Teams v Slack

Slack has been a poster-child for the consumerisation of enterprise software, bringing peer to peer chat to companies. Microsoft augmented its core product, Office365 by acquiring Skype in 2011 and Yammer in 2012.

"Skype Teams integrates deeply with your Office 365 content as well, with the ability to share your calendar inside the app as well as join meetings too. To no surprise, this application is built on the company’s new cloud platform and very well may be the future of Skype for Business"

Microsoft launched Teams in 2016, by leveraging its distribution advantage within Office365, offering organisations the ability to use Slack at additional costs or Teams for free. The results speak for themselves;

Today, Teams has over 75m monthly actives, in contrast to Slack's 12+ million. *there is some debate about how Microsoft account for an active user btw*

Google Meet v Zoom

The most recent examples, and one which Google Calendar users will have noticed. Unfortunately, Alphabet doesn't break out user numbers for Meet. Whilst debate will rage on about whether video conferencing is commoditised - it's evident Google Meet is growing rapidly aided by not only a growing TAM but also by occupying a larger surface area within Google products, namely GSuite.

The core argument for either a break-up or increased regulation of these companies, is based around their ability to cost-effectively dominate existing channels to customers, and saturate them with their new products - stifling innovation.

When does a startup need to focus on distribution?

Most successful outsized companies follow a high-level set of steps to success:

Build a differentiated product, which solves a defined and valuable customer pain point

Understand and prioritise distribution (or product-channel fit) early on. Shift from a product mindset to a mindset of understanding and valuing customer relationships and scalable distribution

Once you have scaled distribution, you're able to become multi-product, either through internal building or through acquisitions

The day zero product build should not take place in a vacuum - understanding customer pain points is key to building a successful product. This means startups need lines of communication to a small cohort (n=<20) of passionate evangelists and early adopters in order to gather feedback. The old trajectory to finding PMF, was;

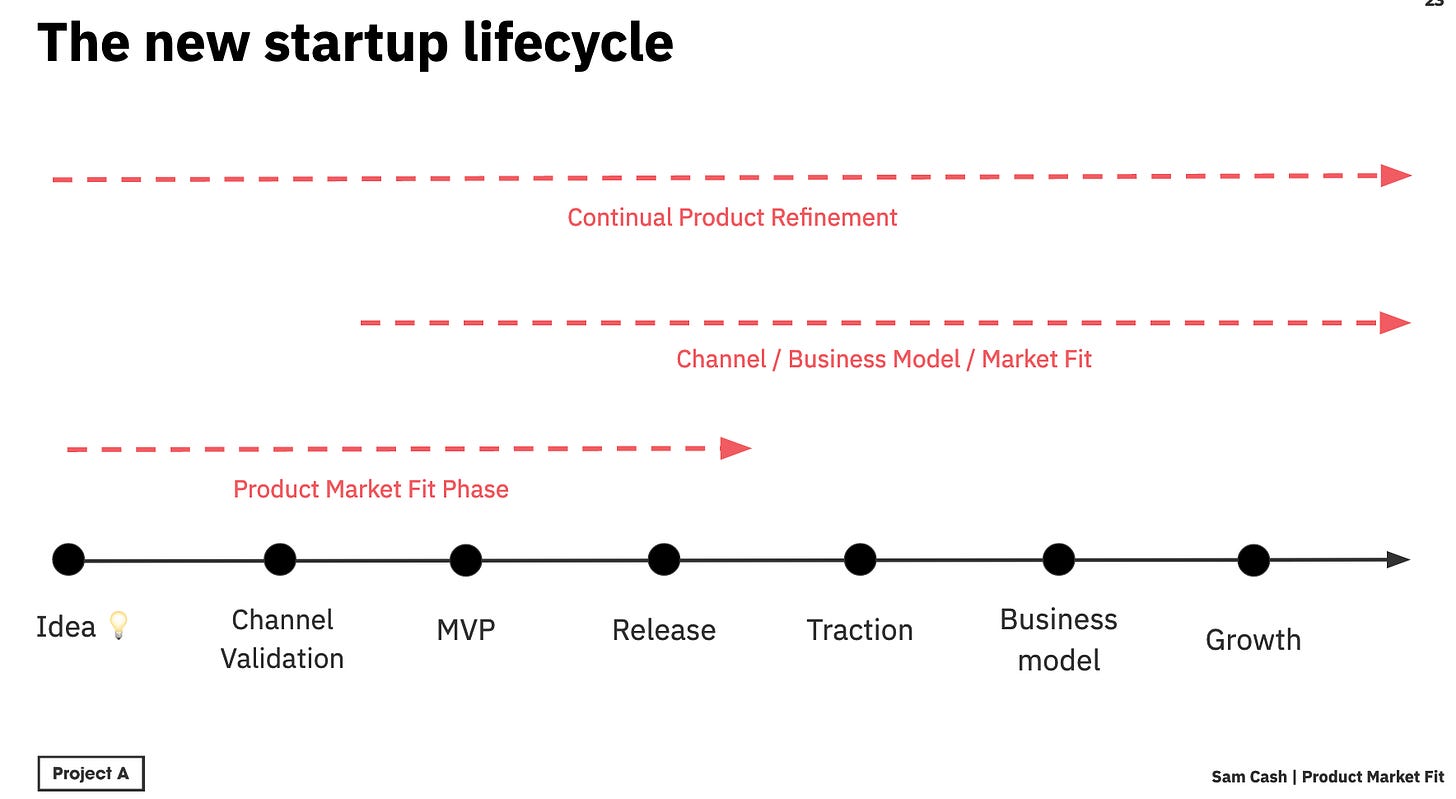

Idea > MVP > Release > Business Model /Channel Fit ->

The new trajectory for finding PMF (below), includes a closer link between early channel validation and the MVP - usually through early testing of marketing channel depth and end user demand.

^^^^ The new trajectory for finding PMF, includes a closer link between early channel validation and the MVP - usually through early testing of marketing channel depth and end user demand.

Danger zone - Post release, founders need to understand that part of their core differentiator and likely their only short term moat is their audience and distribution. Continuing to double down on a pure product-centricity can be fatal. It's not uncommon to see feature creep in companies.

Product remains important but having an eye on scalable channels early on is key. With an increase in heavy SG&A spend, founders need to increasingly have a handle on their distribution levers.

Many of the next batch of category-defining companies will have both product and growth competencies baked into the company from the outset.

Thanks to Luc de Leyritz, Brett Bivens and Gonz Sanchez for the help!

Sam